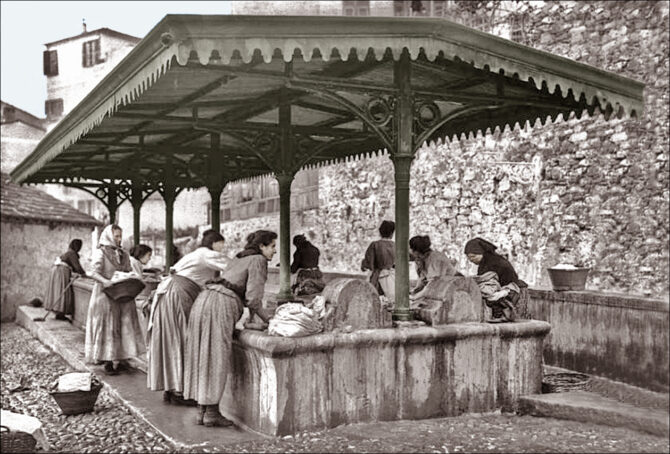

Lavoirs: The History of French Wash-houses

Lavoirs were installed in every French village in the 18th century and these public laundry facilities were as much about community as they were about cleanliness, writes Victoria Gibson

Washing clothes wasn’t always as simple as selecting a cycle and pushing a button. Before running water was so freely available, using a river, fountain or pond would have been normal for such a chore.

However, towards the end of the 18th century when the increase in population and the link between water and serious health conditions was confirmed, public lavoirs began to make an appearance.

The need for dedicated lavoirs was emphasised on 3 February 1851, when the Assemblée Législative voted for a subsidy of 600,000 francs to contribute up to 30% of the construction costs of lavoirs across France.

At least one lavoir was installed in every village and they became just as important as the hôtel de ville or école. The structure was well-planned to ensure it was functional, and some communes even used an architect for its design.

Depending on the location of the lavoir in relation to the river or spring, the washing area would be paved and there would be two basins in total; one for washing and one for rinsing. with a sloped edge for the water to drain away.

Some had the luxury of a chimney to provide ash for the bleaching process and hanging areas to store laundry on. Here, the linens were completely soaked, then doused in boiling water and soap. Once rinsed, the load was twisted and folded then beaten with a wooden battoir against stone slabs.

The women would have a ‘carrosse‘ or ‘cabasson“, a wooden box filled with a soft material such as straw, that protected them from the water and provided some relief to their knees. But this was more than just housework-It was a social event.

Some washing could take place every day and bigger loads, such as bedding. would be done once or twice a year, which could take all day or sometimes three days, known as ‘buées“.

Men were banned from the lavoirs and the women of the village would meet, put the world to rights, sing and of course, air one’s dirty laundry- the opposite to what Napoleon advised in 1815: “Il faut laver son linge sale en famille“.

The invention of the washing machine and its popularity during the middle of the 20th century made lavoirs redundant. Although that’s not to say they’re not in use or forgotten. They are part of the cultural heritage in France and villages are passionate about conserving their history.

Madame Marguerite Décard of the Société pour la Protection des Paysages et de l’Esthétique de la France (SPPFF), explains that the preservation of “petit patrimoine” responds to a double challenge: “Preservation of the historical testimony (memory of historical events, memory of ancient practices, ancient techniques, ancient social functioning etc.),” and “Preservation of the aesthetic quality of the environment: the quality of the natural and built landscape must be preserved so that the inhabitants of a town, a territory or a country can live in a quality environment, a guarantee of a quality life.”

There are currently 67 active lavoir restoration projects listed on the Fondation du patrimoine website (fondation- patrimoine.org) and in 2017, French television channel TF1 broadcast a story about 78-year-old Madame Francine Recouvreur, who refuses to buy a washing machine and still washes her linens in the municipal lavoir of her commune in Haute-Marne. She was dubbed la dernière lavandière de Sommermont (the last washerwoman of Sommermont). And perhaps Madame Recouvreur is not the last…

Do you enjoy learning about French culture and history?

France Today is the world’s leading travel and lifestyle title about France, with a magazine and website written for a truly international audience of educated Francophiles

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email