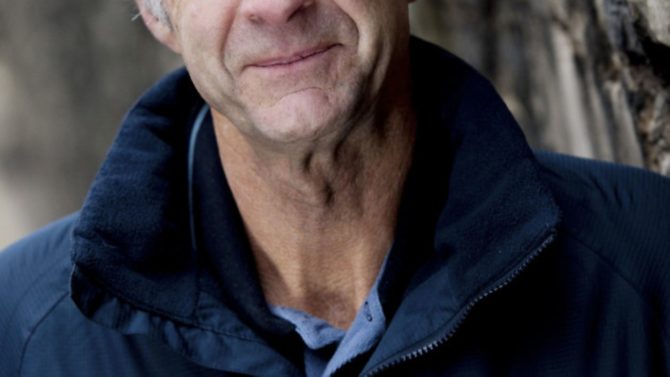

An interview with Sir Ranulph Fiennes

The explorer and author tells Eleanor O’Kane how his French ancestors helped to shape history on both sides of the Channel

In your book Agincourt you highlight the role of your ancestors at the battle. However, the Fienneses were crossing the Channel to wage warfare long before 1415.

You can go back as far as Count Eustache – or Cousin Eustace, as I call him. He was a count of Boulogne and was related to the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor. William (later William the Conqueror) wished to claim what he saw as his right to be king of England. He had no ships, however, whereas Cousin Eustace had a fleet, so the deal was that Eustace would attack with a force of Normans, a handful of boulonnais and some Gascons. If you look at the Bayeux Tapestry you can see Eustace carrying the Norman flag, even though he wasn’t Norman.

Did the military aspects of Agincourt fascinate you as much as the personal connections?

It struck me that it was more like when I’m getting an expedition ready. In my case, we didn’t have very much money when we were getting the big expeditions going so we took months and even years to prepare, knowing that when we were ready we’d have to leave on a specific date because of the ice behaviour. These men had the same problems because in those days ships could sink very easily, so you had to get a very good July date for crossing the Channel. And they had to make three-and-a-half million arrows, each one taking half an hour, so that’s a lot of preparation.

Did you find any living Fienneses in France?

I really wanted to find some French Fiennes but there weren’t any. The residents of the village [of Fiennes in Pas-de-Calais] know that the Fienneses had commanded the French army. The commandant of the French army is known as the constable (connétable); his name was Robert Fiennes and he commanded at the Battles of Crécy and Poitiers [in 1346 and 1356 respectively]. In both battles it was the English and Welsh longbows that defeated Robert Fiennes. The last French Fiennes was another Robert, the nephew of the constable; he was killed at Agincourt.

Was it strange reading about these historic events from both sides?

When I was writing the book I very often found myself doing so from the perspective of the French rather than the English. I suppose one goes with the underdog, although with both lots of Fienneses you can take your pick.

How did you come to be awarded your French parachute wings in 1968?

When I was in the army I was sent to train at the École des troupes aéroportées de Pau (ETAP) alongside 1,200 French men with crewcuts.

I didn’t understand some of the parachute language and made mistakes. One night I understood that we were going to do a water landing; as I descended I could see the white area and followed the procedure for a water landing. It turned out to be ground mist and I landed in a bad way, but I couldn’t complain.

Having seen so much of the world, what do you think of France?

I love it. I think the French are great, even the Parisians! When I was a student I used to hitch-hike over there with my Scottish cousin; we visited the castles of the Loire. We both had kilts so we used to wear them and hope we’d get picked up because from behind we looked like women. When that didn’t work we both put on headscarves!

Agincourt by Ranulph Fiennes is published by Hodder and available in paperback priced £8.99; www.hodder.co.uk

Like this? Check out our other celebrity interviews here

Like French history? Check out our history section for more historical features

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email