Carol Drinkwater: Christmas in Provence

Across Provence traditional santons start to appear in homes and at Christmas markets. Carol Drinkwater explains what these figures are and how they came to be a Provençal Christmas tradition

The days are slipping away; nights are drawing in; shadows are lengthening; the hoot of the owls is more haunting. For many the approach of winter is a time of sadness, of loss. Les feuilles mortes (Autumn Leaves) is one of the greatest popular songs in the French and English languages. With French lyrics penned by the poet Jacques Prévert, it is as rich in melancholy and love lost as the burnished tone of fallen chestnut leaves crinkling and curling on the ground, crunched underfoot.

But here in the Alpes-Maritimes, in this south-east corner of France, we see this shift from late autumn to early winter a little differently. As we drive to and fro, skirting the Mediterranean, watched over by the snow-capped mountains glistening in the sunshine, there is an upbeat mood.

____________________________________________________________________

Related articles

Ian Moore: bringing British traditions to a French Christmas

____________________________________________________________________

We’ll be off to Cagnes-sur-Mer for the resort’s chestnut festival on 19 November. A fun day out if you are here with youngsters; it opens at 11am with the animal parade. Mulled wine and mountain stew, bubbling with chestnuts, are served and there are plenty of stalls offering traditional craftworks.

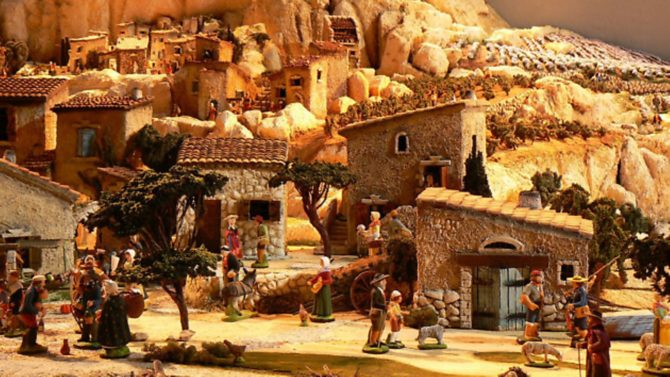

From mid-November until Christmas across the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region you will find various Foires aux Santons. A santon is a Provençal crib figure modelled from baked clay. Santon comes from the Provençal word santoun, meaning little saint.

Buy them completed or to be painted. Chat to one of the santonniers, the artists of the figurines, who will happily give you the history of these local treasures. At the time of the French Revolution, when the churches were closed by the anticlerical revolutionary authorities, nativity scenes were banned. In response, the Provençaux began to make their own cribs – sometimes exhibiting them in their homes for a few centimes. At first, they were formed out of papier mâché, cloth, bread or any material the maker could model. It was an act of faith and revolution, and, if caught, the guillotine could be the reprisal.

The crib figures include, of course, the main players: baby Jesus, Mary and Joseph, but you might also find a shepherdess or glass-blower, a fisherman, knife-grinder, miller, laundry girls, vendors of herbs or fruits, musicians, donkeys, goats, the local curé, even the schoolmistress. It forms a miniature re-enactment of 19th-century Provençal country life.

____________________________________________________________________

Related articless

The 13 traditional desserts eaten at Christmas in Provence

12 reasons to spend Christmas in France

____________________________________________________________________

In 1797, in Marseille, an artisan by the name of Jean-Louis Lagnel (1764-1822) had the idea of creating the figures in clay and painting them. It was in Aubagne at the start of the 20th century that the clay was fired to make the figures more resistant.

Santonniers are usually born into a family business passed down from generation to generation. What is remarkable is that even 21st-century artisans will spend hours in the hills hunting for thyme twigs, a stone or some precise detail they need to give their characters authenticity. Aubagne, birthplace of the great storyteller and film-maker, Marcel Pagnol, boasts an excellent santon museum.

Curiously, one crib figure I have never seen is the olive picker. Curious because, just a few kilometres from where the santonniers are unpacking their wares readying themselves for Christmas, another labour of love is getting under way: the olive harvest.

Climb the winding hills and spot the wooden ladders resting against gnarled trunks. Round our way, most farmers pick by hand and eschew chemicals, leaving our drupes to fatten and ripen naturally. November, for us, is the toil before the Christmas gift of green-golden olive oil. Come and join us.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email