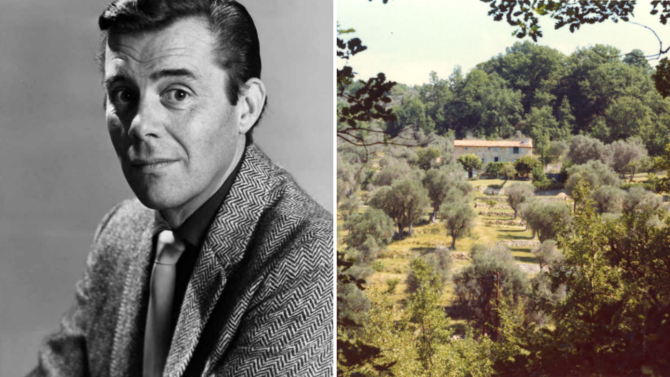

Dirk Bogarde’s France: the legendary actor’s happy place

Discover the legendary actor’s long-time love for Provence, where he owned a 17th-century farmhouse

Reviewing his life in 1990, Dirk Bogarde wryly summarised his existence thus: “At 17 an art student; at 19 scrubbing out pots in the tin wash at Catterick camp [wartime service]; at 27 ‘a film star’ and at 50, deciding to take stock and readjust the seasoning of life, I left England for Provence and sat up on a mountain among my olives and sheep very contentedly.”

But what had led this quintessential British film star to France? As recalled in his acclaimed autobiography, Sussex offered a halcyon childhood but other memories evoked “early days when we came to France each summer for cherished holidays which marked me forever with a deep and undying love for the country. Long ago I’d decided that, when the time was right, I would seek out a place there and stay for good.”

It was 1970 and the cultured Bogarde, once dubbed ‘the idol of the Odeons’ was disenchanted with British cinema, longing for fresh challenges. Invited by director Luchino Visconti to appear in Death in Venice, a seminal film marking his successful transition to European cinema, Dirk and longtime companion Tony Forwood decided to move abroad. And, as Bogarde’s perceptive biographer John Coldstream emphasises, “so began the happiest period of Dirk’s life. Most of the surface gloss applied through stardom had now… been peeled away and the days to come would be enjoyed in the sort of uncluttered simplicity which had characterised his childhood.”

THE CALL OF PROVENCE

It was to a quiet corner of Provence, high up in the hills near Grasse, that he headed, intent on an abode offering solace and space yet not easily accessible. Le Haut Clermont was a 17th-century farmhouse, possessing a bucolic charm and sense of history that captivated Bogarde: “I was instantly in love… It stands on the slope of a hill among 12 acres of giant olives… and looks right down the plain to the bay of La Napoule. Sheerest beauty, half an hour from Nice airport and 30 minutes from Cannes.” From the upstairs former hay loft, a view of “the sea shining some way off like a sheet of silver paper” was visible.

For Bogarde, a man of considerable artistic ability, the beautiful light keenly appealed. He reflected: “Magic has its components and… without this it is fair to say the Riviera would not exist…. This is why Monet and Renoir came, determined to capture ‘the Light’ and set it on canvas.” After a mistral had cleared rain clouds one day he recorded “a light to break one’s heart – of such beauty. This is why we came to Clermont”.

As he describes in the memoir An Orderly Man, Clermont fitted perfectly into his vision “as smoothly and effortlessly as a foot into a well-worn slipper. I knew I had found my ideal”. With an architect’s aid he reshaped the house, honouring its character while enhancing comfort. To Patricia, wife of director Joseph Losey with whom Bogarde had worked on The Servant, he expounded, “It is really rather fine. We have… opened up walls and doors and generally transformed a stable, workroom and kitchen into a 50-foot room with a great terrace.” Here a steady stream of guests visited during the summer months, drawn to what John Coldstream calls, “a house of immaculate taste which always exuded warmth.”

A WRITER’S RETREAT

Writing rather than acting took principal focus. Encouraged to pen his autobiography Bogarde used the former olive studio as his study, the house’s only nod to his profession being photos on the study wall. To his editor Norah Smallwood he mused, “Isn’t it strange to love a place so deeply?” His adopted country bestowed the distinction of Chevalier de l’Ordre de Lettres plus the honour of being the first British President of the Cannes Festival jury in 1984. Only Tony Forwood’s advancing ill-health could disrupt the idyll and there were several false starts before “the heavens all of a sudden fell,” and Clermont was very reluctantly sold in 1986, England beckoning.

But Bogarde would return to France, albeit posthumously, as his beloved nephew Brock Van Den Bogaerde explains: “In the early 1970s I spent my summer hitchhiking and camping in the south of France. Knowing that I might need rescuing, my father gave me the address of Uncle Dirk. The address continued to smolder in my rucksack until one morning, in sweltering heat, curiosity got the better of me and I found myself outside Le Haut Clermont. I’d only met my uncle once, when a small child, so had no idea what to expect.

“From the gate I could just make out the shape of a farmhouse, among the olive trees, with its red crab shell roof and tall cypress trees. This was an old, unspoiled olive farm on the side of a hill. With a deep breath I followed the path up through the neatly mowed terraces until I heard a dog barking. Daisy, the house boxer, was first to say hello. A man approached and I asked if he was Uncle Dirk? He looked me over, seeing I hadn’t had a bath for days, and said in a dismissive tone, ‘you can pitch your tent there’.

“Don’t you have a bed?” I retorted. We looked at each other… and in that moment I knew we were going to be friends. That was the beginning of a friendship where little by little, over many wonderful years, he gave more and more of himself. I was not to know then that I was standing on the very spot where one day I would be trusted to scatter his ashes and return him to his beloved France.”

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Living in France