How to discover the history of your French property

Are you curious about when your French house was built and who else has lived there? Find out how to discover the history of your French property

Local historian Anton Lee lives in Nouvelle-Aquitaine and blogs for Beaux Villages Immobilier

The first thing to say about any aspect of historical research undertaken in France is that a firm grasp of the language is vital. That assumed, there are a number of ways in which the history of your house can be traced. The process is likely to be long and difficult, but those rewarding moments of discovery make it all worthwhile.

Research the local area

Your quest will involve a detailed study of the building itself and a search for any written records which might mention your property. Much of the latter can now be done on the internet. In addition, it will be important to discover as much as possible about the area: a visit to the local maison de la presse will probably furnish you with a booklet or two on the history of the surroundings while the local library might have something more substantial.

________________________________________________________________________________

Don’t miss

Things to consider before buying a renovation project in France

We bought a château in the French countryside – and it was a bargain!

________________________________________________________________________________

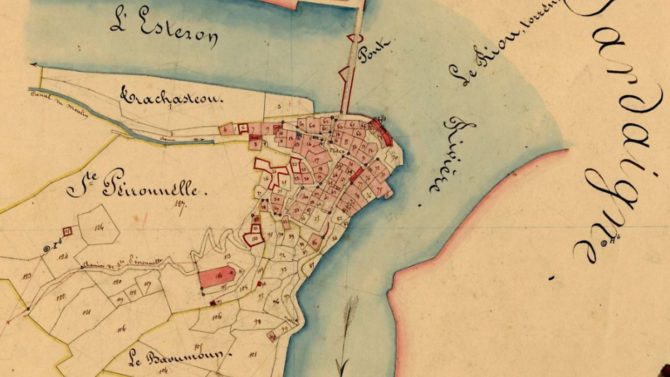

Study old maps

Next are maps; a starting point is your mairie where you should find the Carte Napoléon (sometimes called the carte cadastrale), a detailed, hand-drawn map of every commune, created in the first part of the 19th century. The two great cartographers of the 18th century were Cassini and Belleyme, who covered the whole country and their maps can be looked at online. Almost all country houses and farms will be on one or both if they date from before that time. Old IGN maps (the equivalent of Ordnance Survey) can also help and if you are near a site of historical or geographical interest – an abbey or a river, for instance – you might find other old maps are also available.

Talk to your neighbours

Another invaluable source of information is stories told by neighbours. It is surprising how often families who have been in the locality for a while will have familial links with a number of houses. They may even know of someone who has old photographs. The danger is that a certain amount of misinformation will probably be included as well.

Examine the building

A physical examination of your house is a great place to start. Unless you live in a castle, abbey or converted church, your home is unlikely to go back further than the late 16th century. Apart from the structures mentioned, houses in both town and country between the Roman occupation and the Renaissance were built of timber and daub and have either disappeared or been completely rebuilt.

Make a site plan and try to work out the way the building has developed, because there are very few old houses that have not been altered, often many times. If the house is built of stone, a useful project is to measure the thickness of all the walls. This might help in tracing alterations to the plan. As a general rule of thumb, the thicker the wall, the older it is.

Likewise, openings can be instructive. The general rule, at least with windows, is that the smaller they are, the older. Such investigations should tell you, for instance, whether your maison de maître is from the 19th century or whether a façade has been added to an older building. There are considerable regional differences in France and it will be important to acquaint yourself with the styles of building in your area.

________________________________________________________________________________

Don’t miss

Renovating a property in France on a budget

What type of French property do you want to buy?

________________________________________________________________________________

Look for mentions of your property in local registers

With written records, much will depend on the type of property you are researching. If the house is old, out in the country and has a name, then you are likely to find rich rewards in the état civil for your area. These are the registers of births, deaths and marriages.

From 1539, parishes were obliged to keep records of all these. Before the Revolution the parish priest kept the records; after 1789, the maire of the commune was responsible. Those covering the last hundred years are usually available in your local mairie and are detailed and informative. Anyone can inspect them and the secretary will usually be happy to photocopy whatever interests you. Older records will be kept in the departmental archives and the websites for these are easy enough to find (just type ‘archives départementales’ into your search engine). The difficulty is that these sites are seldom user-friendly and finding what you need can be time-consuming. The état civil can also be examined on microfilm at the archive centres.

Once you have located the records for your village or town, prepare yourself for a long haul. They are unlikely to go back as far as 1539 and there will probably be gaps where folios have been lost, but they may well start towards the end of the 17th century and there will be hundreds if not thousands of records to trawl through.

Obviously, the older they are, the more difficult they are to decipher. Some priests’ handwriting can be little more than a scrawl; others are meticulous. Written French has changed remarkably little over the last three centuries, however, and once you are into your stride you will find them easier to interpret. Information in the earliest records is often scratchy. You are looking for the names of houses and people and, in many parts of rural France, the houses bear the family name of their first occupants. Note that spellings can vary considerably and there may be several names which are confusingly similar.

The records tend to follow a formula which changes periodically over the centuries. The earliest are basic, such as: “third May sixteen ninety-nine so-and-so died having received the sacraments and I buried him in the churchyard the next day”. Marriages are more detailed, giving parents’ names and where they lived. Most records were witnessed and this can give more names, and sometimes addresses. Town houses had no numbers until comparatively recently and you have a distinct advantage if you are researching a named, rural property. Not all departments are available though: some have not yet been uploaded; others were destroyed during the two world wars.

And always expect the unexpected…

Other documents which might help are lawyers’ records (archives de notaires), military lists (registres militaires), newspapers, aerial photographs and census returns. These searches often throw up curve balls For example, a recent search of a farmhouse in Aquitaine started promisingly with the discovery of a bricked-up door and window, both of which had chamfered edges. This, plus the fact that they were in a stone wall nearly a metre thick, were a fairly clear indication of a late Renaissance origin. But the written records for the parish made no mention of the house until the 18th century. The chance discovery of a document written in 1697 by the commander of a nearby hospital run by the Knights of St John, however, revealed that he and the neighbouring seigneur had exchanged two parcels of land in that same year. The house concerned was in one of those parcels and the records for its earlier years were therefore in the état civil for the neighbouring parish.

Like this? You might enjoy:

7 reasons to buy a French property to renovate

Which areas of France are least popular with British buyers

7 things to consider before buying a listed property in France

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email